Yesterday I finished the 540-piece globe puzzleball I got for Christmas (and haven't even opened up until a couple of days ago). Here are a few pictures of it in the process of being built:

And here it is, completed:

There was one piece missing in the south Pacific ocean when I took this picture, but I found it later.

As a puzzle it's interesting and challenging, but the oceans, which cover an awful lot of Earth's surface (and when you do it in globe form, it's clear it's even more than you're expecting even if you know the statistics), are inordinately hard. It would have taken me weeks if I hadn't used the numbers on the back of the pieces for some parts of the ocean. I don't think there's any way to correct for this.

Near the end it gets crazy hard to press the pieces into place because you can't get your hand inside to press against the back. I tried to make up for it a bit with a long-handled wooden spoon, but it's too clumsy to really do the job. There's an easy solution that I'm surprised the manufacturers haven't hit on. Split the puzzle into two puzzles, one per hemisphere, and have the equatorial "edge" pieces have tabs to snap into one another. Then you have all the freedom you need to work on the two halves with full access, to make sure each piece fits securely. At the end, you slip the two halves together to make a full globe. This would work with all their spherical puzzles, not just the earth globe.

Though it's kind of fragile, I can now treat the completed puzzle as a desk globe. I just need to decide where to put it.

Monday, May 31, 2010

Sunday, May 30, 2010

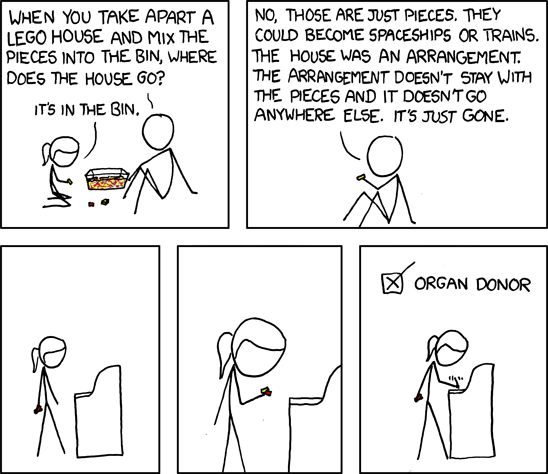

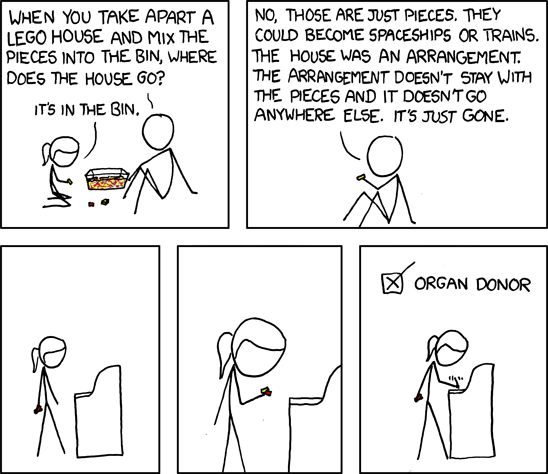

Modern mind-body dualism

The concepts of soulism and Cartesian mind-body dualism are so ubiquitous that all our thoughts are shaped by them. Those with even a basic grounding in philosophy will have these ideas so entrenched that, even when opposing them, they are taking on the stance of going against establishment, rallying against cultural assumptions. And most people who have no idea what I'm talking about have the ideas even deeper in their thoughts, they're just less aware of them.

But these concepts were formed at a time (almost all of human existence) where the idea of something immaterial was so vague that it was unavoidably entangled with mysticism. The soul is explicitly described as a non-physical thing, and yet, it is treated as if it were a physical thing that just happens to be made of a different sort of physical substance. It is, above all, a thing. Less so the mind of Cartesian dualism; in this concept we get halfway to the idea of what we now consider the mind to be, but only halfway. The mind may not be a physical thing, but it's still a thing.

If, somehow, we could have gotten to this point in technological history without finalizing the ideas of soulism or mind-body dualism, and we were only inventing the idea now -- or, to put it another way, if some child could somehow grow up today familiar with modern technology yet wholly innocent of culturally established memes about dualism, then invent his own philosophy -- the resulting dualism would be a thousand times more apt, because for the first time in history, there's a convenient, handy analogy that leads us in what I think is more the right direction. Just as the camera helps us understand the eye (and, if the analogy is taken too far, can lead to misimpressions), the computer can help us understand the brain. And for the first time, everyone is familiar with software, and how it exists as an ephemeral, emergent property, partially independent of yet entirely dependent upon the underlying hardware.

The intangible thing that coexists with the physical thing no longer needs to be some mystical spark, or possess inexplicable properties because of its noncorporeality. The mind is simply software: it is information, it is a particular configuration of the hardware. It is tangible in the sense that the shape of a building you built out of Legos is tangible, and intangible in the sense that those same Legos can be taken apart and built into an airplane, and where is the house now? The mystery is not nearly so mysterious now that we all have in our pockets a six-ounce, $100 bit of metal and plastic that can do the same transcendent mystery as the mind in the brain.

What kind of philosophy would we create if we had this far clearer, much less misleading analogy to start from? To be sure, it would lead us to other spurious conclusions, but I tend to think far less of them, and not as grievous.

But these concepts were formed at a time (almost all of human existence) where the idea of something immaterial was so vague that it was unavoidably entangled with mysticism. The soul is explicitly described as a non-physical thing, and yet, it is treated as if it were a physical thing that just happens to be made of a different sort of physical substance. It is, above all, a thing. Less so the mind of Cartesian dualism; in this concept we get halfway to the idea of what we now consider the mind to be, but only halfway. The mind may not be a physical thing, but it's still a thing.

If, somehow, we could have gotten to this point in technological history without finalizing the ideas of soulism or mind-body dualism, and we were only inventing the idea now -- or, to put it another way, if some child could somehow grow up today familiar with modern technology yet wholly innocent of culturally established memes about dualism, then invent his own philosophy -- the resulting dualism would be a thousand times more apt, because for the first time in history, there's a convenient, handy analogy that leads us in what I think is more the right direction. Just as the camera helps us understand the eye (and, if the analogy is taken too far, can lead to misimpressions), the computer can help us understand the brain. And for the first time, everyone is familiar with software, and how it exists as an ephemeral, emergent property, partially independent of yet entirely dependent upon the underlying hardware.

The intangible thing that coexists with the physical thing no longer needs to be some mystical spark, or possess inexplicable properties because of its noncorporeality. The mind is simply software: it is information, it is a particular configuration of the hardware. It is tangible in the sense that the shape of a building you built out of Legos is tangible, and intangible in the sense that those same Legos can be taken apart and built into an airplane, and where is the house now? The mystery is not nearly so mysterious now that we all have in our pockets a six-ounce, $100 bit of metal and plastic that can do the same transcendent mystery as the mind in the brain.

What kind of philosophy would we create if we had this far clearer, much less misleading analogy to start from? To be sure, it would lead us to other spurious conclusions, but I tend to think far less of them, and not as grievous.

Saturday, May 29, 2010

Surrogates

The reviews of Surrogates were largely negative, and I can see why, but they're mostly a matter of expectations calibration. (Minor spoilers ahead, but they really won't impact your appreciation of the movie, they're all things you'll see coming, particularly if you've seen the trailer which gives away the final scene.)

The reviews of Surrogates were largely negative, and I can see why, but they're mostly a matter of expectations calibration. (Minor spoilers ahead, but they really won't impact your appreciation of the movie, they're all things you'll see coming, particularly if you've seen the trailer which gives away the final scene.)The premise of the movie is that everyone lives through robotic surrogates that look just like people, and which they remotely control from a "stim-chair" back in the safety of their home. This is a fascinating premise in a lot of ways. The many ways this would be used, the benefits and disadvantages, the impact on society, the whys and wherefores of how it could come to be this way (and why the inefficency, compared to a simulated world, makes perfect sense), are ripe for exploration.

That's where the movie falls down, though. Apart from a few throwaway lines and plot points, none of that is explored. We do have one person trying on a body of the opposite gender, and a few people using "enhanced" bodies, but by and large, everyone just looks like themselves, only better-looking and in better shape, and everyone can do the same things they would normally do, only with better endurance and less worry about injury.

A few issues of the threats implicit in this possibility are glossed over. There's a casually tossed-off line about how you can't just jump into someone else's surrogate because they have to be carefully matched to your nervous system -- and then this gets ignored pretty much from then on. The communications between surrogate and stim-chair aren't even encrypted, and all route through a single central switchboard that can tap into or override them at will -- we take more precautions than that with email. Even the central threat -- a weapon that scrambles a surrogate so thoroughly it also scrambles the human behind it -- is glossed over.

Ultimately what we have as fairly serviceable action/suspense movie that only takes its "hook" as far as it needs to to get you to notice it, and then ignores it thenceforth. There's good production values, lots of scenery for Bruce Willis to chew up, a smattering of good action, and enough plot to keep you working it out in your head -- not because you won't see the twists coming like a freight train at night in a cornfield, but because you will need to at least keep a scorecard.

The one place that they do dig up the premise is to make begging-the-question "arguments" about how this technology sucks the humanity out of humanity. They do this by simply presenting it as a fait accompli: a few people have used it to escape from things they should be facing, or find it's "not for them", and while lip service is paid to the good side (the virtual elimination of disease, death due to injury, and most prejudice based on bodies; vast reduction in crime; restoring full functionality to the disabled; and more), ultimately this is all deemed unimportant compared to a few people feeling less alive instead of more alive this way, and some blurry first-year-liberal-arts-major sentimentality.

Compare this movie to Strange Days and it will make you ache, because Strange Days does better as an action movie, and as a mystery, and as a character piece, and still manages to find time to give its similarly-scoped central premise a really thorough workout and exploration, finding both the good and bad uses. (It's hard to avoid the comparison when both movies feature a dreadlocked, black cult-of-personality character who is the de facto leader of an insurrection against the current order of society, too).

So in the end Surrogates is barely a tenth of the movie it could have been, if they'd really spent any thought on their premise, or given it a fairer, less dismissive analysis. But the movie it is, is okay for filling up a few idle hours when you're not looking for much. Expect that, instead of what the ads want you to think the movie is, and you'll be fine.

Friday, May 28, 2010

How would an implant computer change my life?

I'm still very ready for an implant computer. And for just about every step between what I have now and that. But it's hard to make really complete and accurate predictions about how such a thing would really change our lives. Most predictions of the impact of technology on the future make the mistake of taking what we would use it for in today's environment and projecting that onto tomorrow, rather than considering how that act also changes the environment itself. Ask someone in 1980 what Google would do to the world and you'd be likely to get answers focused on how to use Google to solve 1980's problems, but nothing about the many ways ubiquitous access to robust search has changed the kind of things we do, not just the way we can do them. And implant computers would be like that ten times as much.

My first reaction is to think of doing the things I do now, but more ubiquitously, and more efficiently. So instead of wondering something, I could look it up, no matter what I was doing or where. Not just because I was curious ("who was that in that movie?" still comes up while driving down the highway...) but whenever I need information to do whatever I'm doing (imagine how much easier travel would be with ubiquitous access to maps, GPS, flight time updates, restaurant reviews, and my calendar, right in my brain). Instead of trying to remember to do something, I could make a note right then, as easy as thinking; or just do it, depending on the task and my circumstances. I could fill in all those vacant times, like riding in the car or waiting for people, with writing, coding, exercising, or doing any number of other things that don't use up my mind.

My first reaction is to think of doing the things I do now, but more ubiquitously, and more efficiently. So instead of wondering something, I could look it up, no matter what I was doing or where. Not just because I was curious ("who was that in that movie?" still comes up while driving down the highway...) but whenever I need information to do whatever I'm doing (imagine how much easier travel would be with ubiquitous access to maps, GPS, flight time updates, restaurant reviews, and my calendar, right in my brain). Instead of trying to remember to do something, I could make a note right then, as easy as thinking; or just do it, depending on the task and my circumstances. I could fill in all those vacant times, like riding in the car or waiting for people, with writing, coding, exercising, or doing any number of other things that don't use up my mind.

See how I'm just doing what I do with technology today, but in more times and places, and with some inconveniences (like having to use a keyboard) removed? The next step then is to think of new things an implant computer would let me do. One of my favorites is HUD-style "augmented reality". Walk down the street and overlaid on my view would be information about the people and places I'm seeing. This shop has 78% positive reviews and is currently having a sale on such-and-such an item I have flagged on my wish list. That person walking towards me is identified by facial recognition as someone I met at a meeting last year at work, so I can respond appropriately if she greets me. As I drive, "turn left in 100 feet" is replaced by a highlight on the actual route I need to be taking, along with emphasis on important things (like stop signs and pedestrians) and de-emphasis on unimportant things (advertising signs filtered out automatically... or replaced by better advertising for those willing to pay enough for it). Anything I'm looking at, from a menu at a restaurant to a national monument, becomes a hyperlink I can drill down to find out the calorie content or historical significance (respectively, one would hope).

But I wouldn't be the only one with an implant computer. That's where things get really hard to predict. Once implant computers are in common usage, that woman is not going to be impressed that I recognized her a year later; she'll take it for granted, since she also has an implant computer and is currently looking at my Facebook page (by then, maybe Facebook will finally have figured out privacy). Would my boss expect me to be working 18 hours a day since I am "plugged in" that long? Would it be impossible to play in trivia games (or would they invent a new form of trivia to suit it)? What would advertisers be doing to try to take advantage of implant computers to make sales? How could con artists use their implant computers for cons -- since simply adapting them to the old cons would be helpful only for a little while, until we all got used to using ours to avoid those cons?

We've barely scratched the surface of ways that implant computers would change society, and we already see that the ways an implant computer are far larger than anything you'd think of by just taking what you do with a smartphone, laptop, or iPad now, and extending it by removing the keyboard and adding ubiquitous connectivity.

My first reaction is to think of doing the things I do now, but more ubiquitously, and more efficiently. So instead of wondering something, I could look it up, no matter what I was doing or where. Not just because I was curious ("who was that in that movie?" still comes up while driving down the highway...) but whenever I need information to do whatever I'm doing (imagine how much easier travel would be with ubiquitous access to maps, GPS, flight time updates, restaurant reviews, and my calendar, right in my brain). Instead of trying to remember to do something, I could make a note right then, as easy as thinking; or just do it, depending on the task and my circumstances. I could fill in all those vacant times, like riding in the car or waiting for people, with writing, coding, exercising, or doing any number of other things that don't use up my mind.

My first reaction is to think of doing the things I do now, but more ubiquitously, and more efficiently. So instead of wondering something, I could look it up, no matter what I was doing or where. Not just because I was curious ("who was that in that movie?" still comes up while driving down the highway...) but whenever I need information to do whatever I'm doing (imagine how much easier travel would be with ubiquitous access to maps, GPS, flight time updates, restaurant reviews, and my calendar, right in my brain). Instead of trying to remember to do something, I could make a note right then, as easy as thinking; or just do it, depending on the task and my circumstances. I could fill in all those vacant times, like riding in the car or waiting for people, with writing, coding, exercising, or doing any number of other things that don't use up my mind.See how I'm just doing what I do with technology today, but in more times and places, and with some inconveniences (like having to use a keyboard) removed? The next step then is to think of new things an implant computer would let me do. One of my favorites is HUD-style "augmented reality". Walk down the street and overlaid on my view would be information about the people and places I'm seeing. This shop has 78% positive reviews and is currently having a sale on such-and-such an item I have flagged on my wish list. That person walking towards me is identified by facial recognition as someone I met at a meeting last year at work, so I can respond appropriately if she greets me. As I drive, "turn left in 100 feet" is replaced by a highlight on the actual route I need to be taking, along with emphasis on important things (like stop signs and pedestrians) and de-emphasis on unimportant things (advertising signs filtered out automatically... or replaced by better advertising for those willing to pay enough for it). Anything I'm looking at, from a menu at a restaurant to a national monument, becomes a hyperlink I can drill down to find out the calorie content or historical significance (respectively, one would hope).

But I wouldn't be the only one with an implant computer. That's where things get really hard to predict. Once implant computers are in common usage, that woman is not going to be impressed that I recognized her a year later; she'll take it for granted, since she also has an implant computer and is currently looking at my Facebook page (by then, maybe Facebook will finally have figured out privacy). Would my boss expect me to be working 18 hours a day since I am "plugged in" that long? Would it be impossible to play in trivia games (or would they invent a new form of trivia to suit it)? What would advertisers be doing to try to take advantage of implant computers to make sales? How could con artists use their implant computers for cons -- since simply adapting them to the old cons would be helpful only for a little while, until we all got used to using ours to avoid those cons?

We've barely scratched the surface of ways that implant computers would change society, and we already see that the ways an implant computer are far larger than anything you'd think of by just taking what you do with a smartphone, laptop, or iPad now, and extending it by removing the keyboard and adding ubiquitous connectivity.

Thursday, May 27, 2010

Transitory to-do lists

I've got that kind of personality that is called "pathologically organized" by people who can't find their keys and forgot to pay the electric bill. I make a lot of lists. My smartphone is always, always on my person, so I can jot down additions to my various to-do lists any time something occurs to me, and so I can review what's the next thing to do.

But that's still not enough. I regularly find myself, on getting up to do something, having to make a list of items to do on this trip, summarizing each one with a word, and then repeating the string of words to myself, because it's not worth it to write them down when it's just one little trip around the house, but I will lose items otherwise. Maybe it's a sign of my advancing age, though it seems like I've been doing this for many years.

But that's still not enough. I regularly find myself, on getting up to do something, having to make a list of items to do on this trip, summarizing each one with a word, and then repeating the string of words to myself, because it's not worth it to write them down when it's just one little trip around the house, but I will lose items otherwise. Maybe it's a sign of my advancing age, though it seems like I've been doing this for many years.

I wonder if someone would be puzzled or amused to hear me walking around saying "bug-spray helmet jacket harness gloves" over and over -- or maybe even more so for a list that fits together less well, like "charge soda load headset slippers." But if I heard someone else doing something like that, I'd just nod knowingly at the kindred spirit.

The thing is, I never do. Maybe it's just me.

But that's still not enough. I regularly find myself, on getting up to do something, having to make a list of items to do on this trip, summarizing each one with a word, and then repeating the string of words to myself, because it's not worth it to write them down when it's just one little trip around the house, but I will lose items otherwise. Maybe it's a sign of my advancing age, though it seems like I've been doing this for many years.

But that's still not enough. I regularly find myself, on getting up to do something, having to make a list of items to do on this trip, summarizing each one with a word, and then repeating the string of words to myself, because it's not worth it to write them down when it's just one little trip around the house, but I will lose items otherwise. Maybe it's a sign of my advancing age, though it seems like I've been doing this for many years.I wonder if someone would be puzzled or amused to hear me walking around saying "bug-spray helmet jacket harness gloves" over and over -- or maybe even more so for a list that fits together less well, like "charge soda load headset slippers." But if I heard someone else doing something like that, I'd just nod knowingly at the kindred spirit.

The thing is, I never do. Maybe it's just me.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Attitudes about curing diabetes

A recent visit to the eye doctor bumped me up against the contradiction at the heart of the medical community's attitude towards diabetes.

It has been an uphill battle for doctors to get people to understand that diabetes is a chronic, lifelong condition. Most people have a vague notion that you just have to avoid sugar and take your medicine every few hours, and you're fine. Diabetes usually appears in movies as an excuse for a character to need their medicine now Now NOW NOW or they'll die! (when for the vast majority of diabetes sufferers, the only immediately life-threatening need they'll face is a need for food if they took their insulin a little while ago and then missed the planned meal).

At least, that's how it was ten years ago. Nowadays, while Hollywood still insists on using diabetes as a ticking time bomb plot device, huge increases in the rate of diagnosis mean most people know someone who is diabetic and probably have picked up a little bit more about it, and lots of public education has also made a dent. People have gotten the message that diabetes requires a lifetime of care. There's more awareness of being "prediabetic" (which is often a euphemism, sometimes for "you're diabetic, but we think you'll be better motivated to take care of it if we call it this instead", and sometimes for "you need to eat better and exercise more, and this is a way to strike some fear into you"). And this public education also includes educating the medical community; while gastroenterologists might be up on these things, your GP might lag a while, and your dentist probably learns about it the same way you do.

So just about when they're getting us to take diabetes seriously and understand it, a complication arises. It turns out that there has been evidence for a few decades now that gastric bypasses can resolve -- that is, "cure" -- diabetes. This has been known for a long time but not publicized even within the medical community for the simple reason that no one really understands precisely how it works. It's also very easy to misunderstand. "Fat people get diabetes. Gastric bypass makes you lose a lot of weight. Ergo, the loss of weight is how it works." Well, no. It turns out that in the majority of cases, diabetes measures like blood sugar drop precipitously in the first few weeks after the surgery, long before there's been enough weight loss to matter (losing that same amount of weight by other means would not be expected to, and does not, lead to significant changes in blood sugar levels). Something fundamental and metabolic changes, probably something to do with the extensive nervous system around the stomach (almost as complex in scale as the brain, yet barely understood), that leads to an almost immediate resolution.

We get stuck in a bit of semantics at this point. After gastric bypass, am I "cured", or is my diabetes merely in "long-term remission"? Yes, it's possible in ten years I could become diabetic again, particularly if I find ways to regain a lot of the weight. But if I had never been previously diagnosed and someone checked me out now, my fantastically normal blood sugar levels would soundly put me into the class of "not diabetic, not even at high risk to be diabetic". I don't really have a higher risk of becoming diabetic than someone else of my current weight who hadn't been through being diabetic and having a gastric bypass -- in fact, probably less, since regaining the weight, though possible, is less likely.

We get stuck in a bit of semantics at this point. After gastric bypass, am I "cured", or is my diabetes merely in "long-term remission"? Yes, it's possible in ten years I could become diabetic again, particularly if I find ways to regain a lot of the weight. But if I had never been previously diagnosed and someone checked me out now, my fantastically normal blood sugar levels would soundly put me into the class of "not diabetic, not even at high risk to be diabetic". I don't really have a higher risk of becoming diabetic than someone else of my current weight who hadn't been through being diabetic and having a gastric bypass -- in fact, probably less, since regaining the weight, though possible, is less likely.

The insurance companies still treat diabetes as a life-long condition, and we don't argue the point too strenuously because that makes them more likely to authorize some things that the doctors ask for, that are probably no longer needed. That's where my eye doctor's office comes in. They still want us to come in for an annual checkup, because that's standard procedure for diabetics, even though our blood sugar levels are probably better than 90% of their never-been-diabetic patients. They don't quite come out and say "no you aren't" when we refer to ourselves as "cured" but it's clear that that's how they think of it. They haven't gotten the news, or aren't convinced of it; and they treat us like we're oversimplifying or being in denial. They're very polite about it, in fact, exceedingly friendly, cheerful, and upbeat, praising us for our sugar levels, our weight loss, our exercise regimens, and the condition of our eyes (particularly mine, which remain perfect at the age of 42), but it's still there.

I guess they had to fight a long time to get people to take diabetes adequately seriously, and understanding it as a permanent condition that is, at most, "in control," was a big part of that, so they're loathe to let it go. No one wants to be the first to say "cured" officially (except the people who do the gastric bypasses, and even they are cagey about it), because of the fallout (both legal and in terms of public perception) if they end up wrong.

Yet the evidence keeps mounting. Even the ADA, which is notoriously conservative (still recommending the high-carb diet that has been proven time and again to be bad for diabetics), has come close to calling it a 'cure' by now. In the end, my blood sugar is probably lower than that of the majority of people around me, including skinny, athletic, unabashedly "healthy" people; and my risk of diabetic complications is as low as theirs, or lower. What's the real point of calling me "a diabetic in remission"? To "trick" me into exercising? Maybe for some people that works, though it's a sad commentary if it does.

It has been an uphill battle for doctors to get people to understand that diabetes is a chronic, lifelong condition. Most people have a vague notion that you just have to avoid sugar and take your medicine every few hours, and you're fine. Diabetes usually appears in movies as an excuse for a character to need their medicine now Now NOW NOW or they'll die! (when for the vast majority of diabetes sufferers, the only immediately life-threatening need they'll face is a need for food if they took their insulin a little while ago and then missed the planned meal).

At least, that's how it was ten years ago. Nowadays, while Hollywood still insists on using diabetes as a ticking time bomb plot device, huge increases in the rate of diagnosis mean most people know someone who is diabetic and probably have picked up a little bit more about it, and lots of public education has also made a dent. People have gotten the message that diabetes requires a lifetime of care. There's more awareness of being "prediabetic" (which is often a euphemism, sometimes for "you're diabetic, but we think you'll be better motivated to take care of it if we call it this instead", and sometimes for "you need to eat better and exercise more, and this is a way to strike some fear into you"). And this public education also includes educating the medical community; while gastroenterologists might be up on these things, your GP might lag a while, and your dentist probably learns about it the same way you do.

So just about when they're getting us to take diabetes seriously and understand it, a complication arises. It turns out that there has been evidence for a few decades now that gastric bypasses can resolve -- that is, "cure" -- diabetes. This has been known for a long time but not publicized even within the medical community for the simple reason that no one really understands precisely how it works. It's also very easy to misunderstand. "Fat people get diabetes. Gastric bypass makes you lose a lot of weight. Ergo, the loss of weight is how it works." Well, no. It turns out that in the majority of cases, diabetes measures like blood sugar drop precipitously in the first few weeks after the surgery, long before there's been enough weight loss to matter (losing that same amount of weight by other means would not be expected to, and does not, lead to significant changes in blood sugar levels). Something fundamental and metabolic changes, probably something to do with the extensive nervous system around the stomach (almost as complex in scale as the brain, yet barely understood), that leads to an almost immediate resolution.

We get stuck in a bit of semantics at this point. After gastric bypass, am I "cured", or is my diabetes merely in "long-term remission"? Yes, it's possible in ten years I could become diabetic again, particularly if I find ways to regain a lot of the weight. But if I had never been previously diagnosed and someone checked me out now, my fantastically normal blood sugar levels would soundly put me into the class of "not diabetic, not even at high risk to be diabetic". I don't really have a higher risk of becoming diabetic than someone else of my current weight who hadn't been through being diabetic and having a gastric bypass -- in fact, probably less, since regaining the weight, though possible, is less likely.

We get stuck in a bit of semantics at this point. After gastric bypass, am I "cured", or is my diabetes merely in "long-term remission"? Yes, it's possible in ten years I could become diabetic again, particularly if I find ways to regain a lot of the weight. But if I had never been previously diagnosed and someone checked me out now, my fantastically normal blood sugar levels would soundly put me into the class of "not diabetic, not even at high risk to be diabetic". I don't really have a higher risk of becoming diabetic than someone else of my current weight who hadn't been through being diabetic and having a gastric bypass -- in fact, probably less, since regaining the weight, though possible, is less likely.The insurance companies still treat diabetes as a life-long condition, and we don't argue the point too strenuously because that makes them more likely to authorize some things that the doctors ask for, that are probably no longer needed. That's where my eye doctor's office comes in. They still want us to come in for an annual checkup, because that's standard procedure for diabetics, even though our blood sugar levels are probably better than 90% of their never-been-diabetic patients. They don't quite come out and say "no you aren't" when we refer to ourselves as "cured" but it's clear that that's how they think of it. They haven't gotten the news, or aren't convinced of it; and they treat us like we're oversimplifying or being in denial. They're very polite about it, in fact, exceedingly friendly, cheerful, and upbeat, praising us for our sugar levels, our weight loss, our exercise regimens, and the condition of our eyes (particularly mine, which remain perfect at the age of 42), but it's still there.

I guess they had to fight a long time to get people to take diabetes adequately seriously, and understanding it as a permanent condition that is, at most, "in control," was a big part of that, so they're loathe to let it go. No one wants to be the first to say "cured" officially (except the people who do the gastric bypasses, and even they are cagey about it), because of the fallout (both legal and in terms of public perception) if they end up wrong.

Yet the evidence keeps mounting. Even the ADA, which is notoriously conservative (still recommending the high-carb diet that has been proven time and again to be bad for diabetics), has come close to calling it a 'cure' by now. In the end, my blood sugar is probably lower than that of the majority of people around me, including skinny, athletic, unabashedly "healthy" people; and my risk of diabetic complications is as low as theirs, or lower. What's the real point of calling me "a diabetic in remission"? To "trick" me into exercising? Maybe for some people that works, though it's a sad commentary if it does.

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

Whatever happened, happened.

I'm fairly sure this is spoiler-free, even if you haven't watched since season one.

Since the final episode of Lost started at 9pm on a Sunday night, I couldn't watch it live, though I wanted to. Wondering how it would end kept me from getting a good night's sleep on Sunday night; I kept dreaming scripts, usually involving it crossing over with other shows or other storylines, because these are dreams and they have to involve something surrealistic and absurd.

We watched it right after work yesterday. And I can say that I am entirely satisfied. No, they didn't answer every fiddly tiny detail question, but they answered all the questions that they needed to answer. Even some of the fiddly details that we despaired about ever getting answers to, I think they're there and we're still finding them. (I read a very interesting observation about the Hanso Foundation today that provided explanation for how a lot of seasons two through four fit into the larger story, for instance.)

We watched it right after work yesterday. And I can say that I am entirely satisfied. No, they didn't answer every fiddly tiny detail question, but they answered all the questions that they needed to answer. Even some of the fiddly details that we despaired about ever getting answers to, I think they're there and we're still finding them. (I read a very interesting observation about the Hanso Foundation today that provided explanation for how a lot of seasons two through four fit into the larger story, for instance.)

Some things that are not explained are intentionally not explained because they are part of the premise: the story just happens to happen in a world where things like this are true. No one asks for an explanation for why Melinda can see ghosts, or why there even are ghosts, in Ghost Whisperer: it just happens to happen in a world where there are ghosts, and some people can see them. In the same way, some properties of the Island, and some other things like what Miles can do, are just how things work in this world, and while we do get explanations for what they are and how they work, we don't get explanations for why they are this way. Compare to how much better Star Wars was when the Force was the thing which binds the universe together, to when it was some nonsense about symbiont midichlorians. (And even that didn't explain anything, just pushed the question one level deeper.)

On top of having a satisfying resolution to the mysteries, the finale also had a satisfying resolution to the plot. The conflicts were drawn into sharp focus and then resolved. The challenges were built up to a climax and the tension ratcheted up, then the payoff made it all seem like it meant something. Even more, the characters were satisfyingly resolved, with each of the people we'd cared about given a chance to find completion, with some of the most tear-jerking, and entirely sincere, moments on TV in recent memory.

During the first couple of seasons, I considered Lost a really good show, well worth watching, though if it were cancelled I wouldn't've wept. Later, as they misstepped with the season about the Others, I got close to considering dropping it, and there were episodes I didn't pay strict attention to. Later seasons cranked things right back up, including the mystery and the complexity, but even more so, the characters. The show became more important to me again, but even coming into the final season, I didn't think of it as a favorite show. A few episodes this season were fantastic, but at no point did I even consider that this could be on my favorite shows of all time list at all.

Maybe it's just the emotional impact of the final episode being so fresh, but the way it all wrapped up just tied it so tightly in a bow, it feels like it retroactively made so much of what passed on the way here so much better that I am thinking it's probably on my top ten favorite shows of all time list. I haven't actually made such a list: I only know with certainty what numbers one and two are. If I took the time to make such a list it would probably be full of moments with me musing, oh, wait, that show belongs on it too, and maybe by time I was done Lost would have fallen off the top ten contenders list entirely. But even if that's so, it's remarkable that I'm even considering it now, when a week ago, it didn't even occur to me to ask the question.

Incidentally, the fact that I was at least half right, and more right than any other person I know of, in my theory about what was going on this season, probably isn't hurting either.

Since the final episode of Lost started at 9pm on a Sunday night, I couldn't watch it live, though I wanted to. Wondering how it would end kept me from getting a good night's sleep on Sunday night; I kept dreaming scripts, usually involving it crossing over with other shows or other storylines, because these are dreams and they have to involve something surrealistic and absurd.

We watched it right after work yesterday. And I can say that I am entirely satisfied. No, they didn't answer every fiddly tiny detail question, but they answered all the questions that they needed to answer. Even some of the fiddly details that we despaired about ever getting answers to, I think they're there and we're still finding them. (I read a very interesting observation about the Hanso Foundation today that provided explanation for how a lot of seasons two through four fit into the larger story, for instance.)

We watched it right after work yesterday. And I can say that I am entirely satisfied. No, they didn't answer every fiddly tiny detail question, but they answered all the questions that they needed to answer. Even some of the fiddly details that we despaired about ever getting answers to, I think they're there and we're still finding them. (I read a very interesting observation about the Hanso Foundation today that provided explanation for how a lot of seasons two through four fit into the larger story, for instance.)Some things that are not explained are intentionally not explained because they are part of the premise: the story just happens to happen in a world where things like this are true. No one asks for an explanation for why Melinda can see ghosts, or why there even are ghosts, in Ghost Whisperer: it just happens to happen in a world where there are ghosts, and some people can see them. In the same way, some properties of the Island, and some other things like what Miles can do, are just how things work in this world, and while we do get explanations for what they are and how they work, we don't get explanations for why they are this way. Compare to how much better Star Wars was when the Force was the thing which binds the universe together, to when it was some nonsense about symbiont midichlorians. (And even that didn't explain anything, just pushed the question one level deeper.)

On top of having a satisfying resolution to the mysteries, the finale also had a satisfying resolution to the plot. The conflicts were drawn into sharp focus and then resolved. The challenges were built up to a climax and the tension ratcheted up, then the payoff made it all seem like it meant something. Even more, the characters were satisfyingly resolved, with each of the people we'd cared about given a chance to find completion, with some of the most tear-jerking, and entirely sincere, moments on TV in recent memory.

During the first couple of seasons, I considered Lost a really good show, well worth watching, though if it were cancelled I wouldn't've wept. Later, as they misstepped with the season about the Others, I got close to considering dropping it, and there were episodes I didn't pay strict attention to. Later seasons cranked things right back up, including the mystery and the complexity, but even more so, the characters. The show became more important to me again, but even coming into the final season, I didn't think of it as a favorite show. A few episodes this season were fantastic, but at no point did I even consider that this could be on my favorite shows of all time list at all.

Maybe it's just the emotional impact of the final episode being so fresh, but the way it all wrapped up just tied it so tightly in a bow, it feels like it retroactively made so much of what passed on the way here so much better that I am thinking it's probably on my top ten favorite shows of all time list. I haven't actually made such a list: I only know with certainty what numbers one and two are. If I took the time to make such a list it would probably be full of moments with me musing, oh, wait, that show belongs on it too, and maybe by time I was done Lost would have fallen off the top ten contenders list entirely. But even if that's so, it's remarkable that I'm even considering it now, when a week ago, it didn't even occur to me to ask the question.

Incidentally, the fact that I was at least half right, and more right than any other person I know of, in my theory about what was going on this season, probably isn't hurting either.

Monday, May 24, 2010

Revised MAME cabinet plans

Though I started with the plans for a MAME cabinet from the Ultimate MAME site, I decided to make some significant adaptations to suit my monitor and control panel plans.

Though I started with the plans for a MAME cabinet from the Ultimate MAME site, I decided to make some significant adaptations to suit my monitor and control panel plans.The original plans were for a cathode ray tube monitor of considerable size, actually much, much larger than original arcade game monitors. The monitor I got is a 22" HDTV with a very slender profile. It wouldn't fit the space provided in any dimension; it's a bit too narrow, a lot too short, and very very much shallower, plus it's a 16:9 instead of 4:3 aspect ratio. Hence, I used a bit of trigonometry to reduce the size while keeping the same angle.

The original plans call for building a control panel, but I intend to buy one fully assembled from MAMEroom. It's a fair bit smaller than the original plans, but since it's not built into the plans, I decided to adjust the plans to make the space where the control panel goes a little deeper to better fit it. This might need adjustment after I buy the control panel next month, but for now, the plans will fit the depth and height of the panel. (The width will stick off a bit to either side, but that's typical for MAME cabinets.)

The original plans call for building a control panel, but I intend to buy one fully assembled from MAMEroom. It's a fair bit smaller than the original plans, but since it's not built into the plans, I decided to adjust the plans to make the space where the control panel goes a little deeper to better fit it. This might need adjustment after I buy the control panel next month, but for now, the plans will fit the depth and height of the panel. (The width will stick off a bit to either side, but that's typical for MAME cabinets.)I also reduced the width of the whole cabinet by six inches in order to better fit the width of the monitor. That way, it'll fit the monitor so that there's no space showing on either side. I might put in a bit of a bezel to frame it, but I might just leave it showing as is, since it's a pretty nice front.

Finally, since I don't need clearance for the depth of a cathode ray tube, I was able to make a significant reduction in the cabinet's depth, and simplify the shape: there's no need for the slope at the top rear anymore. The resulting cabinet is about 26" deep instead of 40" deep, but still has gobs of room for the stuff that'll go into it. It's also about 5" shorter, but that's not going to make much difference.

It should fit my components better, be a little simpler to build, take up less space, and still allow plenty of room to access the equipment. I won't start building until after I buy the control panel next month. Though I might dig out one of my old retired computers and try setting up MAME on it to see if they're up to the task, or if I need to buy a cheap computer next time one comes up on Woot.

Sunday, May 23, 2010

Bridal shower versus bachelor party

Admittedly, the bachelor party I'm planning and hosting is not your ordinary bachelor party. No scantily-clad girls will be jumping out of any cakes or dancing around any poles, and the most potent potable there will be diet Pepsi. Instead of the usual fare, we're going to play lazer tag, miniature golf, and arcade games at Pizza Putt through one of their group event plans. But all in all this is probably about the same amount of work and complexity to plan as the more traditional version.

.jpg) By contrast, the bridal shower which is going on at my house later today (as of this writing, Saturday, May 22), seems like planning and carrying out an invasion. The whole preceding week has been a flurry of housecleaning and moving furniture and shopping. Between decorations, party favors, cleaning supplies, and food, we've had to do a ton of shopping for this event, and it's not even finished. There's cooking to be done, too. There were games and events to plan and prepare for. Later today, we have to move most of the living room furniture out into other rooms, and rearrange most of what's left. I'll have to take the dog out for four or five hours and find somewhere to occupy her that won't involve her going nuts or digging up anyone's yard, which means I'll have to stay on the move, most likely. And when it's all done we have to move all the furniture back.

By contrast, the bridal shower which is going on at my house later today (as of this writing, Saturday, May 22), seems like planning and carrying out an invasion. The whole preceding week has been a flurry of housecleaning and moving furniture and shopping. Between decorations, party favors, cleaning supplies, and food, we've had to do a ton of shopping for this event, and it's not even finished. There's cooking to be done, too. There were games and events to plan and prepare for. Later today, we have to move most of the living room furniture out into other rooms, and rearrange most of what's left. I'll have to take the dog out for four or five hours and find somewhere to occupy her that won't involve her going nuts or digging up anyone's yard, which means I'll have to stay on the move, most likely. And when it's all done we have to move all the furniture back.

All I have to do is set a time, make a reservation, and do a little coordinating of shared rides. Maybe when we get there I'll need to offer a bit of leadership in setting up teams and times for lazer tag, or when to eat the included pizza. I guess I got off easy.

.jpg) By contrast, the bridal shower which is going on at my house later today (as of this writing, Saturday, May 22), seems like planning and carrying out an invasion. The whole preceding week has been a flurry of housecleaning and moving furniture and shopping. Between decorations, party favors, cleaning supplies, and food, we've had to do a ton of shopping for this event, and it's not even finished. There's cooking to be done, too. There were games and events to plan and prepare for. Later today, we have to move most of the living room furniture out into other rooms, and rearrange most of what's left. I'll have to take the dog out for four or five hours and find somewhere to occupy her that won't involve her going nuts or digging up anyone's yard, which means I'll have to stay on the move, most likely. And when it's all done we have to move all the furniture back.

By contrast, the bridal shower which is going on at my house later today (as of this writing, Saturday, May 22), seems like planning and carrying out an invasion. The whole preceding week has been a flurry of housecleaning and moving furniture and shopping. Between decorations, party favors, cleaning supplies, and food, we've had to do a ton of shopping for this event, and it's not even finished. There's cooking to be done, too. There were games and events to plan and prepare for. Later today, we have to move most of the living room furniture out into other rooms, and rearrange most of what's left. I'll have to take the dog out for four or five hours and find somewhere to occupy her that won't involve her going nuts or digging up anyone's yard, which means I'll have to stay on the move, most likely. And when it's all done we have to move all the furniture back.All I have to do is set a time, make a reservation, and do a little coordinating of shared rides. Maybe when we get there I'll need to offer a bit of leadership in setting up teams and times for lazer tag, or when to eat the included pizza. I guess I got off easy.

Saturday, May 22, 2010

The last people to heat spaghetti in a pot

Microwave ovens actually date from the 1950s, but they started to become ubiquitous all at once in the 1970s, when I was quite young. Within a few years we went from where most people hadn't even heard of them, to where anyone of moderate means was trying to figure out where to put one in the kitchen, about as quickly as DVD players made their way into our houses in the 1990s.

Microwaves have been standard equipment in virtually every kitchen for about thirty years now. There are people who have owned several houses and have children who never lived in a kitchen without one.

Microwaves have been standard equipment in virtually every kitchen for about thirty years now. There are people who have owned several houses and have children who never lived in a kitchen without one.

Sometimes I wonder if they look at a can of Spaghetti-Os and wonder, why do they still sell these in metal cans, when virtually everyone who eats Spaghetti-Os is going to heat it in a microwave oven, and yet you can't put the can in the microwave. Wouldn't it make more sense to put it in plastic or something? And of course they do, but only in canisters half the size but which usually cost more, so ultimately, the metal cans (of a typical can size) still remain the largest part of their sales (I assume).

And thinking that made me realize, my generation is the last one to remember when the normal way, in fact almost the only way, to heat up Spaghetti-Os, or canned corn, or virtually anything else in a can that needed heating, was in a pot over the stove. The idea must seem almost as alien as horse-drawn buggies to people just 5-10 years younger than me. In fact, the same is true of heating up most leftovers -- which means that there are tastes that are effectively extinct now, like that unique quality that leftover spaghetti (with sauce) gets when you reheat it in a pot, and it gets a little tough, but not in a bad way -- it's kind of hard to describe, you have to try it.

I suppose that if you really look, everyone can probably find something that their generation was the last to taste or try or do, and the advent of the microwave doesn't make that more true -- just more obvious. I wonder what other transitions like that aren't so evident.

Microwaves have been standard equipment in virtually every kitchen for about thirty years now. There are people who have owned several houses and have children who never lived in a kitchen without one.

Microwaves have been standard equipment in virtually every kitchen for about thirty years now. There are people who have owned several houses and have children who never lived in a kitchen without one.Sometimes I wonder if they look at a can of Spaghetti-Os and wonder, why do they still sell these in metal cans, when virtually everyone who eats Spaghetti-Os is going to heat it in a microwave oven, and yet you can't put the can in the microwave. Wouldn't it make more sense to put it in plastic or something? And of course they do, but only in canisters half the size but which usually cost more, so ultimately, the metal cans (of a typical can size) still remain the largest part of their sales (I assume).

And thinking that made me realize, my generation is the last one to remember when the normal way, in fact almost the only way, to heat up Spaghetti-Os, or canned corn, or virtually anything else in a can that needed heating, was in a pot over the stove. The idea must seem almost as alien as horse-drawn buggies to people just 5-10 years younger than me. In fact, the same is true of heating up most leftovers -- which means that there are tastes that are effectively extinct now, like that unique quality that leftover spaghetti (with sauce) gets when you reheat it in a pot, and it gets a little tough, but not in a bad way -- it's kind of hard to describe, you have to try it.

I suppose that if you really look, everyone can probably find something that their generation was the last to taste or try or do, and the advent of the microwave doesn't make that more true -- just more obvious. I wonder what other transitions like that aren't so evident.

Friday, May 21, 2010

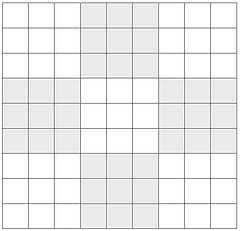

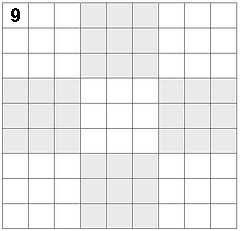

How many sudoku puzzles are there?

I found myself wondering how many possible Sudoku puzzles there are, because, hey, that's the kind of thing I think about when there's nothing else for my brain to be doing. I went through a few approaches trying to figure out how to calculate it, and I'm not totally sure if the one I settled on is valid logic.

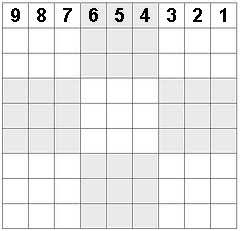

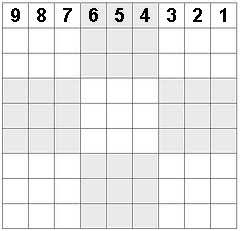

Consider a blank Sudoku puzzle:

Right now, with nothing determined, the upper left cell in the corner can be anything, so it has nine possible values. Let's write a nine there -- not representing that that's the value there, but that's the number of possible values that could be there.

Now let's assume we've figured out what the upper left cell is. That means there's eight possible values for the cell just right of it, and seven for the cell right of that, and six for the next one, and so on.

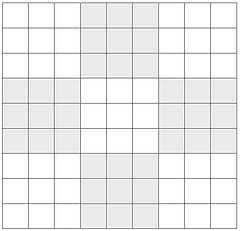

Following the same reason we can fill in more cells with how many possible values there are left for each one, based on the assumption that some valid value is in all the cells we've already filled in:

The order we fill in cells will decide what values end up in each cell, but I am fairly sure (though I probably couldn't prove it with mathematical rigor) that whatever order I choose, all the same values will end up in the grid, just in different places.

So far, I am nearly certain that I've proven something: if you multiply all the numbers written down so far, that's the total number of combinations of values that are possible in the cells that are filled in, in the set of all possible valid Sudoku solutions. (Right now, that's 407,586,816,000 possible grids.)

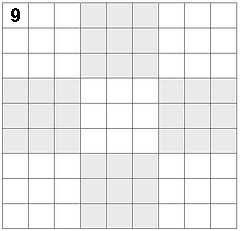

However, at this point it starts getting tricky. Consider the cell in row two, column four. We now know that three other cells in its row have been determined, and three other cells in its square. But we cannot conclude that that only leaves three possible values, since some of those might be the same. In fact, the same three numbers might appear in both groups, leaving six possible values here. But we can't just write in a six and proceed, because there are only six possible here in some of the 407,586,816,000. So we would need to figure out how many of those 407,586,816,000 have six, and how many have five, and how many have four, and how many have three; and then divide up the calculation. If we call those values N6, N5, N4, and N3, it would follow that N6 + N5 + N4 + N3 = 407,586,816,000. The total number of possible Sudoku puzzles with the cells filled in we have so far, and that next cell, would be equal to (6 * N6) + (5 * N5) + (4 * N4) + (3 * N3).

And once we try to do yet another cell, we will further have to bifurcate our calculation, including both those bifurcations, and the further bifurcations possible in that cell. Just a few more cells and this would go far beyond the bounds of calculability. Doing the entire puzzle would be impossible.

I've tried to come up with a different order to fill in the cells that would avoid this, and it's simply not possible. You can go back to the last version pictured above and try finding as many cells as possible you can fill in without a bifurcation, to minimize it. But more than half the puzzle will need bifurcations like this under the best of circumstances, where even three or four bifurcations makes the calculation impossible. So I must conclude my strategy is fundamentally unsound. It devolves into a brute force method too quickly.

The question I can't answer, though, is whether there is a more elegant solution. I suppose I should do a Google search to see who else has attacked the problem, but I'd rather give myself a few days to see if another idea occurs to me -- or if anyone posts some ideas on my comments.

Consider a blank Sudoku puzzle:

Right now, with nothing determined, the upper left cell in the corner can be anything, so it has nine possible values. Let's write a nine there -- not representing that that's the value there, but that's the number of possible values that could be there.

Now let's assume we've figured out what the upper left cell is. That means there's eight possible values for the cell just right of it, and seven for the cell right of that, and six for the next one, and so on.

Following the same reason we can fill in more cells with how many possible values there are left for each one, based on the assumption that some valid value is in all the cells we've already filled in:

The order we fill in cells will decide what values end up in each cell, but I am fairly sure (though I probably couldn't prove it with mathematical rigor) that whatever order I choose, all the same values will end up in the grid, just in different places.

So far, I am nearly certain that I've proven something: if you multiply all the numbers written down so far, that's the total number of combinations of values that are possible in the cells that are filled in, in the set of all possible valid Sudoku solutions. (Right now, that's 407,586,816,000 possible grids.)

However, at this point it starts getting tricky. Consider the cell in row two, column four. We now know that three other cells in its row have been determined, and three other cells in its square. But we cannot conclude that that only leaves three possible values, since some of those might be the same. In fact, the same three numbers might appear in both groups, leaving six possible values here. But we can't just write in a six and proceed, because there are only six possible here in some of the 407,586,816,000. So we would need to figure out how many of those 407,586,816,000 have six, and how many have five, and how many have four, and how many have three; and then divide up the calculation. If we call those values N6, N5, N4, and N3, it would follow that N6 + N5 + N4 + N3 = 407,586,816,000. The total number of possible Sudoku puzzles with the cells filled in we have so far, and that next cell, would be equal to (6 * N6) + (5 * N5) + (4 * N4) + (3 * N3).

And once we try to do yet another cell, we will further have to bifurcate our calculation, including both those bifurcations, and the further bifurcations possible in that cell. Just a few more cells and this would go far beyond the bounds of calculability. Doing the entire puzzle would be impossible.

I've tried to come up with a different order to fill in the cells that would avoid this, and it's simply not possible. You can go back to the last version pictured above and try finding as many cells as possible you can fill in without a bifurcation, to minimize it. But more than half the puzzle will need bifurcations like this under the best of circumstances, where even three or four bifurcations makes the calculation impossible. So I must conclude my strategy is fundamentally unsound. It devolves into a brute force method too quickly.

The question I can't answer, though, is whether there is a more elegant solution. I suppose I should do a Google search to see who else has attacked the problem, but I'd rather give myself a few days to see if another idea occurs to me -- or if anyone posts some ideas on my comments.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

The next generation of GPS

Nowadays we pretty much take for granted that a GPS will include up-to-the-minute road maps, listings of restaurants and gas stations, turn-by-turn directions, on-the-fly rerouting, voice commands, and various trip planning features. Good ones also have voice recognition, the ability to say even street names, can recommend where to get a good price on gas, link to current data about road repairs and weather conditions, and can tie into Web sites about businesses. But it wasn't that long ago that a typical GPS didn't even have maps; you just set waypoints or recorded routes, or at best, prepared routes ahead of time on a PC and dumped them as a series of waypoints into the GPS.

And yet, even today's gee-whiz GPSes don't quite give us the guidance we'd need to be able to find an unfamiliar destination without a navigator, without a bit of luck, in most cities. The last hundred feet are fraught with difficulties, as are the hundred feet before each turn, particularly in cities where the roads come close together so it's not clear which one of the upcoming turns you're being warned about. And there's the issue of where you need to be in the left or right lane.

Some of this can be addressed with improvements in the database of roads, which is a perpetual challenge -- gathering the data of all the roads was a monumental task, so adding a little bit of data to it would be unthinkably duplicative of that challenge. But most of it needs something else that, if it didn't exist, I would imagine it nearly impossible to hope it would become available... but fortunately, it is being gathered right now. Google Streetview.

What a quantum leap it's going to be the first time someone makes a GPS that uses Streetview to not just tell you the turn is coming up, but show it to you. The actual road you're on, with the next turn (or the destination) highlighted. I've seen "maybe in ten years" stuff about augmented reality HUDs in cars to do this, but there's no reason Tomtom couldn't have a model out next month that did this. Putting it on a HUD overlaying reality is super, but really, a 6"-wide color screen on your dashboard with a Streetview image of where you are right now (thus echoing what you see out the windshield) with the next point highlighted, would be 90% of the benefit of HUD, but available with today's technology.

What a quantum leap it's going to be the first time someone makes a GPS that uses Streetview to not just tell you the turn is coming up, but show it to you. The actual road you're on, with the next turn (or the destination) highlighted. I've seen "maybe in ten years" stuff about augmented reality HUDs in cars to do this, but there's no reason Tomtom couldn't have a model out next month that did this. Putting it on a HUD overlaying reality is super, but really, a 6"-wide color screen on your dashboard with a Streetview image of where you are right now (thus echoing what you see out the windshield) with the next point highlighted, would be 90% of the benefit of HUD, but available with today's technology.

Surely Google has thought of this. Maybe they're planning to make Google Maps (or at least the mobile version) do this, once mobile bandwidth is adequate to streaming the images, or something. I can't wait.

And yet, even today's gee-whiz GPSes don't quite give us the guidance we'd need to be able to find an unfamiliar destination without a navigator, without a bit of luck, in most cities. The last hundred feet are fraught with difficulties, as are the hundred feet before each turn, particularly in cities where the roads come close together so it's not clear which one of the upcoming turns you're being warned about. And there's the issue of where you need to be in the left or right lane.

Some of this can be addressed with improvements in the database of roads, which is a perpetual challenge -- gathering the data of all the roads was a monumental task, so adding a little bit of data to it would be unthinkably duplicative of that challenge. But most of it needs something else that, if it didn't exist, I would imagine it nearly impossible to hope it would become available... but fortunately, it is being gathered right now. Google Streetview.

What a quantum leap it's going to be the first time someone makes a GPS that uses Streetview to not just tell you the turn is coming up, but show it to you. The actual road you're on, with the next turn (or the destination) highlighted. I've seen "maybe in ten years" stuff about augmented reality HUDs in cars to do this, but there's no reason Tomtom couldn't have a model out next month that did this. Putting it on a HUD overlaying reality is super, but really, a 6"-wide color screen on your dashboard with a Streetview image of where you are right now (thus echoing what you see out the windshield) with the next point highlighted, would be 90% of the benefit of HUD, but available with today's technology.

What a quantum leap it's going to be the first time someone makes a GPS that uses Streetview to not just tell you the turn is coming up, but show it to you. The actual road you're on, with the next turn (or the destination) highlighted. I've seen "maybe in ten years" stuff about augmented reality HUDs in cars to do this, but there's no reason Tomtom couldn't have a model out next month that did this. Putting it on a HUD overlaying reality is super, but really, a 6"-wide color screen on your dashboard with a Streetview image of where you are right now (thus echoing what you see out the windshield) with the next point highlighted, would be 90% of the benefit of HUD, but available with today's technology.Surely Google has thought of this. Maybe they're planning to make Google Maps (or at least the mobile version) do this, once mobile bandwidth is adequate to streaming the images, or something. I can't wait.

Wednesday, May 19, 2010

All hair colors are hot

What hair color is sexiest on a woman? I have a paradoxical reaction to this question which I can't make any sense of, because they all seem to fit. It's not like I don't have a favorite, and it's not like which one is my favorite changes from day to day. Simultaneously, paradoxically, each of them is my favorite. Which makes no sense and which I can't resolve or even explain. It's like if I think of any one hair color on a woman, I get the same reaction of appreciation you'd expect if it was my favorite hair color, the same one I might get from thinking of some other trait that was particularly of interest to me.

I can't really compare when they all get that reaction. If I try, I can think of a reason for each one. For instance, redheads are exotic for being scarcer, especially more natural shades of red, and that seems like an edge... until I think of one of the other colors, which brushes aside any sense that redheads really have an edge after all. It's like my favorite really is "whichever one I'm thinking of right now" as if I had no more memory than a cat.

I can't really compare when they all get that reaction. If I try, I can think of a reason for each one. For instance, redheads are exotic for being scarcer, especially more natural shades of red, and that seems like an edge... until I think of one of the other colors, which brushes aside any sense that redheads really have an edge after all. It's like my favorite really is "whichever one I'm thinking of right now" as if I had no more memory than a cat.

About the only thing that doesn't get that reaction is the more obviously artificial colorations. Even then, an obviously artificial red sheen on brown hair, or a bottle blonde, isn't too bad, just not as "favorite" as a more natural-looking color. Though go too far into unnatural and it starts to lose appeal. Bubblegum pink is tolerable; green, however, and you've lost me.

I guess I just like hair. Still, it makes no sense to me. I can certainly understand not being able to pick a favorite, but what does it even mean, beyond a meaningless banality, to say they're all favorites? I have a feeling the distinction isn't coming through in this text.

I can't really compare when they all get that reaction. If I try, I can think of a reason for each one. For instance, redheads are exotic for being scarcer, especially more natural shades of red, and that seems like an edge... until I think of one of the other colors, which brushes aside any sense that redheads really have an edge after all. It's like my favorite really is "whichever one I'm thinking of right now" as if I had no more memory than a cat.

I can't really compare when they all get that reaction. If I try, I can think of a reason for each one. For instance, redheads are exotic for being scarcer, especially more natural shades of red, and that seems like an edge... until I think of one of the other colors, which brushes aside any sense that redheads really have an edge after all. It's like my favorite really is "whichever one I'm thinking of right now" as if I had no more memory than a cat.About the only thing that doesn't get that reaction is the more obviously artificial colorations. Even then, an obviously artificial red sheen on brown hair, or a bottle blonde, isn't too bad, just not as "favorite" as a more natural-looking color. Though go too far into unnatural and it starts to lose appeal. Bubblegum pink is tolerable; green, however, and you've lost me.

I guess I just like hair. Still, it makes no sense to me. I can certainly understand not being able to pick a favorite, but what does it even mean, beyond a meaningless banality, to say they're all favorites? I have a feeling the distinction isn't coming through in this text.

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 launched a week after my second birthday, and landed on the moon four days later. My mother told me that it was the first thing I ever showed interest in on the TV; before this, I'd never shown much sign of noticing the TV, though children under the age of two often love staring at it (a friend's baby has been watching Jeopardy since she was under one year old, we hope to recruit her for our trivia team when she grows up). I'm pretty sure my mother said I watched the landing; don't know if I watched the launch, too.

Most likely, it's just a coincidence that, at the age of two years plus a week, I found the moon landing the first good thing on TV, given that I later became fascinated with space and have remained so all my life. But it's certainly tempting to imagine it's not just coincidence. While people don't generally remember anything from before the age of about four to five (though many people think they do, it often turns out to be memories of hearing about events later), we really don't know much about what kind of impressions these events are making on their minds. Maybe it was being fascinated by that broadcast that shaped my mind to be fascinated by the subject later, and all my life.

Most likely, it's just a coincidence that, at the age of two years plus a week, I found the moon landing the first good thing on TV, given that I later became fascinated with space and have remained so all my life. But it's certainly tempting to imagine it's not just coincidence. While people don't generally remember anything from before the age of about four to five (though many people think they do, it often turns out to be memories of hearing about events later), we really don't know much about what kind of impressions these events are making on their minds. Maybe it was being fascinated by that broadcast that shaped my mind to be fascinated by the subject later, and all my life.

Of course, it could be that there was something about me already formed by then which drew me to certain topics, and so this wasn't what caused it, but just an early sign of it. But even if you feel it's possible to have a predilection for space or futurism at the age of two, it's harder to believe that any two-year-old, even a bright one like me, could have really understood what was going on in that TV broadcast enough for that kind of predilection to kick in. At least enough to make a complete change from "totally uninterested in TV" to "staring raptly at the screen through the entire broadcast" (as my mother characterized it -- though she might have been exaggerating).

In any case, I kind of like knowing this about myself. It probably means nothing, and so probably shouldn't be a point of pride, even a minor one, but it certainly can't hurt.

Most likely, it's just a coincidence that, at the age of two years plus a week, I found the moon landing the first good thing on TV, given that I later became fascinated with space and have remained so all my life. But it's certainly tempting to imagine it's not just coincidence. While people don't generally remember anything from before the age of about four to five (though many people think they do, it often turns out to be memories of hearing about events later), we really don't know much about what kind of impressions these events are making on their minds. Maybe it was being fascinated by that broadcast that shaped my mind to be fascinated by the subject later, and all my life.

Most likely, it's just a coincidence that, at the age of two years plus a week, I found the moon landing the first good thing on TV, given that I later became fascinated with space and have remained so all my life. But it's certainly tempting to imagine it's not just coincidence. While people don't generally remember anything from before the age of about four to five (though many people think they do, it often turns out to be memories of hearing about events later), we really don't know much about what kind of impressions these events are making on their minds. Maybe it was being fascinated by that broadcast that shaped my mind to be fascinated by the subject later, and all my life.Of course, it could be that there was something about me already formed by then which drew me to certain topics, and so this wasn't what caused it, but just an early sign of it. But even if you feel it's possible to have a predilection for space or futurism at the age of two, it's harder to believe that any two-year-old, even a bright one like me, could have really understood what was going on in that TV broadcast enough for that kind of predilection to kick in. At least enough to make a complete change from "totally uninterested in TV" to "staring raptly at the screen through the entire broadcast" (as my mother characterized it -- though she might have been exaggerating).

In any case, I kind of like knowing this about myself. It probably means nothing, and so probably shouldn't be a point of pride, even a minor one, but it certainly can't hurt.

Monday, May 17, 2010

The virus alert virus