(If you're reading from the top down, skip down to the first of this three-part series and read them in chronological order instead. It'll work a lot better that way.)Much has been made of the assertion, widely agreed upon by quantum physicists, that determinism as a scientific principle is dead. How's that?

Physics has been getting farther and farther from what makes intuitive sense for a century now. This is not a criticism -- the real world has no obligation to resemble, on the microscopic or macroscopic scales, the everyday world our brains are hardwired to work in and be comfortable with. Relativity gave us such mind-blowing concepts as time dilation and an absolute speed limit, flying in the face of intuition. Quantum mechanics makes relativity look positively tame.

If even Richard Feynman, one of the most gifted minds in history at relating such esoteric things as quantum mechanics to the lay mind, can't make things like the observer effect and the uncertainty principle seem comprehensible, I sure don't stand much of a chance. Any attempt to simplify invariably produces such an abbreviation that it leads people to jump to spurious conclusions based not on the actual science but rather in the gaps in the analogies. So I'm reluctant to even try to explain the relationship of quantum mechanics to determinism. But I can't really proceed without doing so; so read this knowing it's a poor summary at best.

The uncertainty principle says, in a sense, that

information is itself an object in the physical world, that can be conserved, that has an effect. Nearly everyone's heard of the famous paradox of Schroedinger's Cat, in which information changes the world by collapsing a waveform, and many have heard of the problem of Wigner's Friend which furthers this question by asking what, precisely, constitutes an observer. The uncertainty principle, which could be likened to a conversation principle for information, is less well popularized, and just as infuriating.

It says basically that there are pairs of pieces of information which cannot simultaneously be known about a particle. You cannot, for instance, know both a particle's position and its momentum at the same time; the more precisely you know one, the less you know the other.

This tends to make people think it's an engineering problem, the same way people liken the light barrier to the sound barrier and assume someone's just got to come up with a better spaceship design or a more powerful engine to break it. But it's not an engineering problem. It's a fundamental limitation that is part of the very fabric of the universe, and one which has been proven in a large number of mind-numbingly-weird experiments. The universe simply does not allow you to know one of these pieces of information more precisely without making it so you know the other one less precisely, and this precision is a mathematically defined constant (called Planck's constant).

What this means is that, at the atomic scale, particles are effectively not in one place. A particle isn't a glob of stuff somewhere. A particle is better understood as an effect on the world around it, and that effect has only a statistically distributed probability of being seen in various places. This is called the "waveform" of a particle; it says, in a sense, the particle has a 5% chance of being here (or rather, its effect being felt here), a 15% chance of being there, and so on. Certain observations "collapse the waveform" -- force it to reduce itself to a single point with a 100% probability -- but these observations in turn make the particle's

momentum become a more broadly-defined, and finally undefined, waveform. The broader one is, the narrower the other becomes.

That means that on an atomic scale, determinism is not strictly observed. You cannot know the positions and momentums of the particles, so you cannot predict their future states. The best you can do is provide a statistical estimate of the likelihoods of the particles being in various places doing various things. Einstein famously refused to accept this and essentially wasted the second half of his career trying to disprove it; while his efforts were very fruitful in leading other scientists to make important discoveries, and he himself was a key part in the development of some important principles of quantum mechanics (much to his ire), one can't help wonder what he might have accomplished if he hadn't railed so hard against it. (Though the famous quote attributed to him, "God does not play dice with the universe", is a paraphrase; the actual quote is, "I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice", to which Neils Bohr replied, "Einstein, don't tell God what to do".)

On an everyday scale (the scale of grains of sand, ball bearings, and boulders) this lack of determinism almost disappears. Technically speaking, there is still a statistical variability in the position of a grain of sand, or even a planet, because of the uncertainty principle. However, as the randomness in each of the billions of subatomic particles involved tends to balance with the others, the effective precision of our knowledge of the position of an entire grain of sand is so high that the uncertainty can be all but ignored. But it is still there. Technically speaking, even if you knew the precise position, momentum, energy state, etc. of every star in the universe, you could

not predict their future states with perfect precision, only with a statistically enormous probability of correctness.

So technically determinism is dead. Most laypersons who hear about this feel confident that scientists will eventually discover some "hidden variables" that will allow it to be revived, though the more one studies quantum mechanics, the less likely one is to still consider that possible, so it's probably just one of those spurious conclusions I discussed earlier; but it does remain possible, as the history of science is full of surprises.

But does the death of determinism undo any of the changes to the human condition that determinism originated? I say no, and not for the usual reasons (quantum effects are vanishingly small on the macroscopic level), but for a far more fundamental reason. It's true that we can't say with precision where a particle will be, but it's also true that statistically the positions of particles will obey well-defined laws in aggregate. The key point about determinism that made it change everything is that the world behaves as it does because of its own rules, not the whims of unpredictable spirits and gods, and thus an understanding of those rules would allow mankind to foresee and change its future. The position of a particle might not be possible to measure, know, and predict to arbitrary accuracy, but that doesn't change that its behavior in aggregate is governed by knowable and usable rules; it just means those rules include a statistical element, but statistics itself is a science.

One can still know the world. One can still shape the world. There is no going back to the time of spirits. Free will cannot be so readily surrendered.

Cooking directions are full of these helpful statements. "Do not overbake", for instance. Well, duh. Is there anything you are supposed to overbake? If there were, that wouldn't be overbaking. Cooking shows are even worse; you can hardly go an episode of any show, even the good ones, without being told something about how you shouldn't put too much, or not enough, of something into the recipe. That's what "too much" and "not enough" means already; tell us how much to put! Why don't they go the next step and say "When preparing this recipe, be sure not to do anything wrong."

Cooking directions are full of these helpful statements. "Do not overbake", for instance. Well, duh. Is there anything you are supposed to overbake? If there were, that wouldn't be overbaking. Cooking shows are even worse; you can hardly go an episode of any show, even the good ones, without being told something about how you shouldn't put too much, or not enough, of something into the recipe. That's what "too much" and "not enough" means already; tell us how much to put! Why don't they go the next step and say "When preparing this recipe, be sure not to do anything wrong."

Logically, one can conclude that if this is true for a set of ingredients S, it will also be true for any set S' where S is a subset of S'. For instance, if it is true for "chocolate, cheese, garlic, onions" then it's also true for "chocolate, cheese, garlic, onions, spaghetti sauce". So the challenge is not to find a set which makes a true assertion; it's to find the smallest possible set that does so.

Logically, one can conclude that if this is true for a set of ingredients S, it will also be true for any set S' where S is a subset of S'. For instance, if it is true for "chocolate, cheese, garlic, onions" then it's also true for "chocolate, cheese, garlic, onions, spaghetti sauce". So the challenge is not to find a set which makes a true assertion; it's to find the smallest possible set that does so.

RealTime and RTC

RealTime and RTC Prism

Prism Uncreated

Uncreated Bloodweavers

Bloodweavers Foulspawner's Legacy

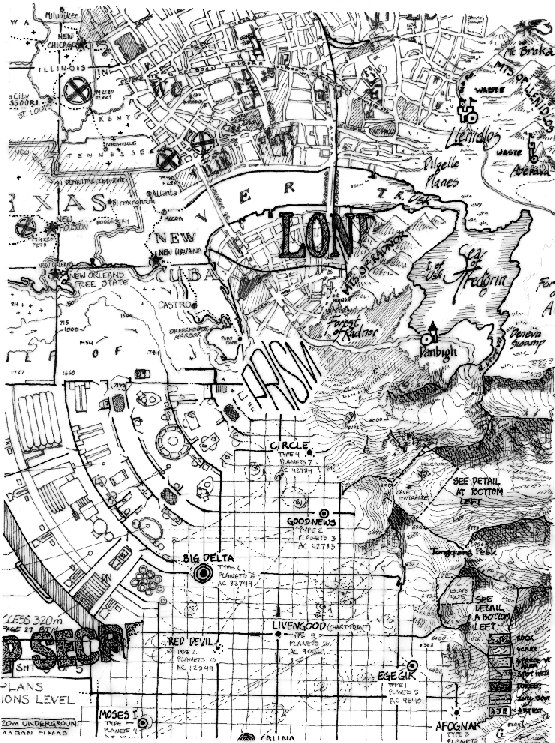

Foulspawner's Legacy Lusternia

Lusternia