But these concepts were formed at a time (almost all of human existence) where the idea of something immaterial was so vague that it was unavoidably entangled with mysticism. The soul is explicitly described as a non-physical thing, and yet, it is treated as if it were a physical thing that just happens to be made of a different sort of physical substance. It is, above all, a thing. Less so the mind of Cartesian dualism; in this concept we get halfway to the idea of what we now consider the mind to be, but only halfway. The mind may not be a physical thing, but it's still a thing.

If, somehow, we could have gotten to this point in technological history without finalizing the ideas of soulism or mind-body dualism, and we were only inventing the idea now -- or, to put it another way, if some child could somehow grow up today familiar with modern technology yet wholly innocent of culturally established memes about dualism, then invent his own philosophy -- the resulting dualism would be a thousand times more apt, because for the first time in history, there's a convenient, handy analogy that leads us in what I think is more the right direction. Just as the camera helps us understand the eye (and, if the analogy is taken too far, can lead to misimpressions), the computer can help us understand the brain. And for the first time, everyone is familiar with software, and how it exists as an ephemeral, emergent property, partially independent of yet entirely dependent upon the underlying hardware.

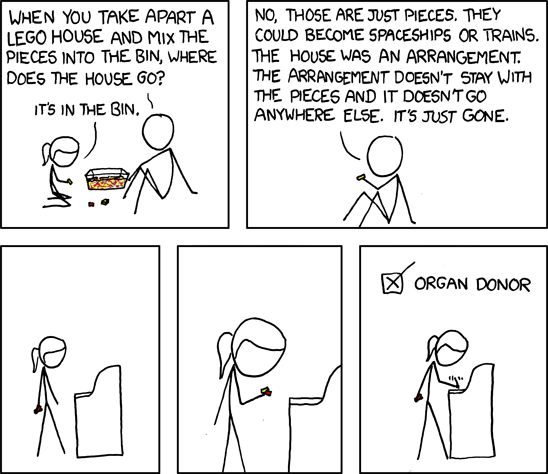

The intangible thing that coexists with the physical thing no longer needs to be some mystical spark, or possess inexplicable properties because of its noncorporeality. The mind is simply software: it is information, it is a particular configuration of the hardware. It is tangible in the sense that the shape of a building you built out of Legos is tangible, and intangible in the sense that those same Legos can be taken apart and built into an airplane, and where is the house now? The mystery is not nearly so mysterious now that we all have in our pockets a six-ounce, $100 bit of metal and plastic that can do the same transcendent mystery as the mind in the brain.

What kind of philosophy would we create if we had this far clearer, much less misleading analogy to start from? To be sure, it would lead us to other spurious conclusions, but I tend to think far less of them, and not as grievous.

RealTime and RTC

RealTime and RTC Prism

Prism Uncreated

Uncreated Bloodweavers

Bloodweavers Foulspawner's Legacy

Foulspawner's Legacy Lusternia

Lusternia

No comments:

Post a Comment