Sometimes I wonder about how much of a difference that makes. It's easy to see how if you're on a city's water system, and it only has so much water coming in, that everyone has to make sure their share is small enough that it doesn't get behind. But you need to go to a bigger picture to think about how individuals conserving water in rural areas are doing any good. After all, isn't all the water I run through my faucet going to end up in my leachfield and thus back in the same soil it came out of to begin with?

Sure, there's no border between my land and my neighbor's land that the water respects, so some of the water coming into my artesian well comes from my neighbor's land, and some of my leachfield seepage is going to neighbors too. One might speculate about whether these are usually in equilibrium, but even if they're not, does my water usage shift the equilibrium? If I use too much water, will more water leave my land than come in? And how do the choices I and my neighbors make affect the water supply for the entire area around me?

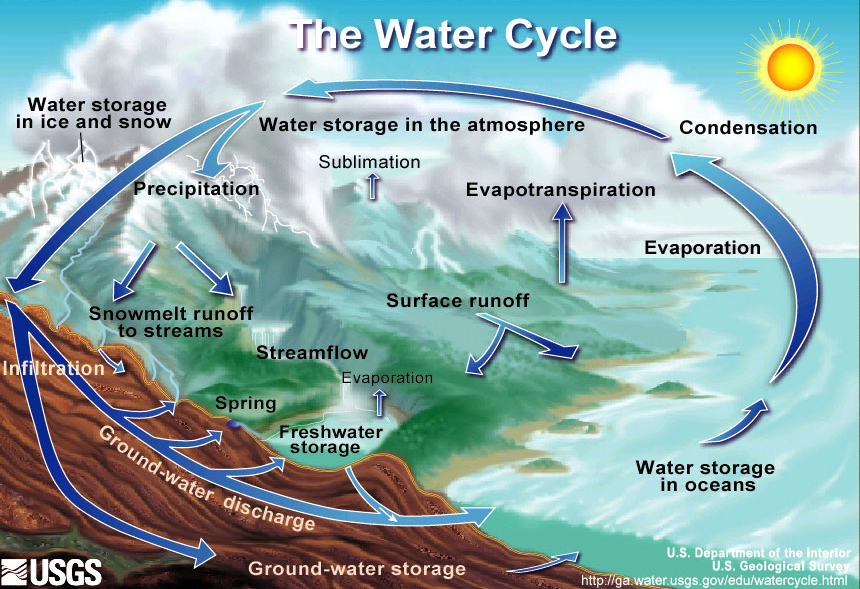

I know very little about the water cycle beyond the very simplistic view we all learned in school (which really doesn't say anything about how human usage patterns affect it, since it's all focused on rain and evaporation). I know enough to know I don't know anything, and to know that if I wanted to spend the time I could learn. But really all I need to know is that, while my water usage might not be as immediately linked to conservation as in the case of someone drawing from a reservoir, it does matter.

I know very little about the water cycle beyond the very simplistic view we all learned in school (which really doesn't say anything about how human usage patterns affect it, since it's all focused on rain and evaporation). I know enough to know I don't know anything, and to know that if I wanted to spend the time I could learn. But really all I need to know is that, while my water usage might not be as immediately linked to conservation as in the case of someone drawing from a reservoir, it does matter.Sometimes the subject of macroeconomics strikes me the same way. When the government spends a lot of money, doesn't that money go back into the economy in much the same way as when individuals spend money, and thus stimulate it? When we talk about giving $4M to Haiti for reconstruction, it's not like we have a reservoir of money and when it runs out it's gone. Turning the faucet and letting $4M of money drain down the sink is part of the process that causes the money to get back into the money cycle and eventually replenish the well from which it came; but it's not very direct, and no one can be entirely sure how to tell how much of it will end up in the reservoir, whether it'll get bigger or smaller by time it gets back, and how that changes depending on where you send it after it comes out.

Of course, and perhaps ironically, we understand the water cycle -- a natural process that predates us by aeons -- better than we understand the money cycle -- an artificial process we ourselves created, albeit emergently. Economists argue endlessly about the relative merits of supply-side and demand-side economics (despite some compelling albeit inconclusive evidence) and the virtues of government spending, but no one can create a miniature yet realistic model of an economy and do experiments on it, so the evidence is always jumbled up with other variables.

And as with the water cycle, rather than get overwhelmed with trying to understand it all when there's so many other topics and so little time, I just do the little bit I know I should do, and take comfort in the fact that there's not much more difference I could make if I knew more, anyway.

RealTime and RTC

RealTime and RTC Prism

Prism Uncreated

Uncreated Bloodweavers

Bloodweavers Foulspawner's Legacy

Foulspawner's Legacy Lusternia

Lusternia

No comments:

Post a Comment