I spent most of this week in Manhattan. It wasn't a vacation, though; I was there for the National Retail Federation's trade show at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, and thus, it was a trip mostly paid for by my employer. (I say only 'mostly' because the travel reimbursement rules are nonsensical. You can only claim a portion of most expenses and then only if you can get a receipt. Per diems are so low they don't even cover anything better than fast food at a Vermont restaurant; in Manhattan, they barely cover tips.)

The trip got off to a bad start when the shuttle company we'd made reservations with (prepaid, in fact) to take us from the airport to the hotel was terrible. They kept us waiting almost an hour, then piled us into an almost-full shuttle. They then shoved two more people in, forcing us to rearrange seats to fit them since I take up too much of a bench seat, which was both inconvenient and a bit embarassing. The ride then took us through a zillion parts of the city that weren't on the way, so all told, it took us two and a half hours from disembarking to get to the hotel. We literally could have walked faster, and the customer service was awful. The guy actually hoped for a tip, too. He didn't get one.

The show itself was productive but exhausting. I visited hundreds of retail suppliers offering everything from receipt printer repair to business analytics consulting services. Along the way I spoke to several companies about the ERP and POS systems we're looking at doing at my office, our methodology and plans and needs, and what kinds of systems exist. I also attended a few informational sessions. The result is, I have a better idea of what kind of things people mean when they talk about what an ERP system does, and I made a lot of contacts with vendors who will help with doing it, or bid on it, or provide information I can use in writing RFPs. I also got a better idea about what the major ERP systems are like and their relative merits and fit to our needs, though that's just a vague sense that won't pay off for a long time. Along the way I also gathered a ridiculous amount of swag, mostly pens that I collected on behalf of a friend who is obsessed with free clicky pens.

The show was crazy huge, filling the entire Javits center, and often it was a solid mob of people and you couldn't get through the hallways. And nearly every single person was dressed in the same drab clothes. On the first day all the women were in boring black too, so that the very few who wore anything else really stood out. Even the "booth babes" (not quite as egregiously so as at things like CES, but still, it was obvious how many of the women working in the booths were chosen not just for tech savvy and salesmanship but also for their looks) were all in drab black on the first day. On the second day, color crept in a bit more, perhaps because a "booth babe" with a hint of blue tended to catch eyes a lot more in that crowd than one who happened to be salaciously curvy yet drably dressed.

I also, for the first time in my career, got feted, wined, and dined by a company, and got to be "the prospect" brought to a fancy restaurant. It was originally going to be a largish dinner with several prospects, but it ended up just three representatives of the suitor company, and me and Siobhan. I went in a button-down shirt and die and with cologne on, but I forgot to take off my hat. They must be wondering about that. The venue was Keen's, a very historical restaurant with good reviews and a nice ambience. The mutton chop was at least a half pound of lamb, of which I ate maybe a fifth, and it was very good lamb. I don't dislike lamb but it's not my favorite thing either; so, really good lamb, maybe the best lamb I ever had, is still only a pretty good meal. But at least now I've had some of the best rated lamb in the world and can safely say, when I say I find lamb to be "eh, okay", that it's not because I haven't tried the good stuff.

Generally speaking, the meals we've had have aimed for the goal of being "stuff we couldn't get elsewhere" and, for me at least, as much about having an experience I wouldn't otherwise get to have, as about the food. A few times we let that slide a bit in favor of being exhausted and taking the easy way out, getting delivery. I actually had fewer chances for good meals than the trip's length might suggest: the hotel had a free breakfast (and a pretty good one, though the scrambled eggs were industrial, but it was a real, hot breakfast), and lunches at the show were quite limited (the food court was terrible, so the second day I packed in a sandwich from a local market), so after you count the two days we were tired and got delivery, and the meal at Keen's, the only remaining full meal was at Empanada Mama -- good empanadas, especially the beef chilli in corn -- and one at Carnegie Deli, about which, more later.

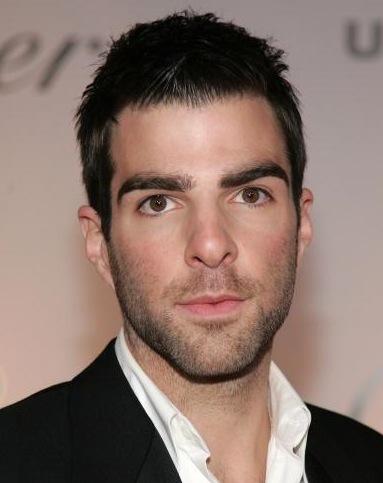

There were also a few smaller nibbles and snacks, but nothing really noteworthy. There was a surprisingly nice hot chocolate with salted peanut butter in it at Shake Shack -- I didn't expect to like it, but I really did. Oh, and speaking of hot chocolate, the one we had at Pigalle was itself nothing special, but the fact that the only other customer in the entire restaurant was Zachary Quinto, dining with two older redheaded women who might have been twins, is certainly noteworthy. Spotting celebrities in NYC isn't totally unusual, and most of the time, most people leave them be -- it's very uncool to be all gushing at them or intrusive. The poor guy was just hanging around having a slice of pie, and I'm sure if I were him I wouldn't want every gawking tourist to be bugging me. So we left him be.

We were scheduled to fly back in the afternoon on Wednesday, but New York was due for a foot of snow, so we were expecting to be delayed. But in the morning we found the storm hadn't been quite as bad as expected. Many flights had been delayed or cancelled, but not ours. However, it seems the brunt of the storm that missed New York hit Vermont, so our flight still ended up being cancelled. That means we're hit right in the purse for the cost of another day in New York, which my employer probably won't cover, so we're stuck with it -- and can't really afford it. (We're still paying off the vow renewal!)

But the good part is, we heard about it

before the shuttle came to take us to the airport, so we were able to salvage most of the day. We got another room at the same hotel, then headed out for a half-day on the town, giving me a chance to see a few sights. Siobhan had been out doing shopping and tourist things the whole trip, but I'd been tied up with the show, and it had left no time for doing fun stuff. So while we can't really afford the extra day, at least I got to spend it doing NYC stuff.

That meant a visit to Carnegie Deli, where we split a knish and a Woody Allen (a huge, and I mean like two pounds of meat, sandwich of corned beef and pastrami). Then we walked through Central Park. In my many visits to the city I'd never gone more than a few blocks into the park, but this time we walked all the way from 59th street to 77th on the west side. Winter isn't the best time to see the park, of course, but at least I've seen some of it. Then we went to Zabar's, where Siobhan strangely didn't buy anything. Finally we took the subway back to the hotel and ordered in Chinese.

Of course, everyone kept telling me, when I speculated on what I might do while in NYC, "go see a Broadway show!" Okay, I get it, to a lot of people that's the best thing you can do in NYC. And our hotel's even in the theater district, a few blocks from Times Square. But almost all the shows in town are big, glitzy musicals, and not a one of them particularly interests me. If they took a couple of hours and were cheap, sure, maybe. But they cost a fortune, and take a ton of time, and dealing with crowds. I don't need that when I'm exhausted and have to get up early. I might do it anyway for something that was amazingly good to me, but just to see an overproduced

La Cage Aux Folles? Not for me.

Then there's the museums. Some of them are great for me -- I always like the Museum of Natural History, for instance, and would have loved to have visited the Hayden Planetarium, which I haven't been to since I was a kid -- but all the art museums really don't do it for me enough to be worth the time and energy. And that's even under normal circumstances. Thanks to recent trips to DC and England, I'm museumed and historied out.

But the trip has made me eager to come back to visit NYC on my own terms, maybe in the summer. Do the midtown walking tour, bicycle around Central Park, go to the planetarium, do some shopping, eat a lot of really cool things I can't get anywhere else, visit some of the more off-the-beaten-path places. Maybe we'll put that farther up on our list of short, less-expensive trips when we can't afford the big overseas trips we've been looking forward to for so long (and just barely made our first foray into last year).

At long last, I have gotten to use my You Rock guitar to play Rock Band 3 in Pro Guitar mode. I only played one song, twice, before I had to give up the TV, but that was enough to get an idea for how much of an adjustment it will be.

At long last, I have gotten to use my You Rock guitar to play Rock Band 3 in Pro Guitar mode. I only played one song, twice, before I had to give up the TV, but that was enough to get an idea for how much of an adjustment it will be.

RealTime and RTC

RealTime and RTC Prism

Prism Uncreated

Uncreated Bloodweavers

Bloodweavers Foulspawner's Legacy

Foulspawner's Legacy Lusternia

Lusternia